When someone dies, they leave behind a lot of stuff. Emotional stuff, yes, but also a shed full of thirty-year-old gardening magazines. To the best of my knowledge, the only time my father ever tried to grow anything was when he bought and planted a rosebush. His definition of gardening was building an electric fence around his flowers to keep the deer from chewing on them. An electric fence seems like overkill, but given that he peered out his front window one night and found a mountain lion on his porch gnawing on a deer haunch, maybe it was warranted.

At least the lion avoided the roses.

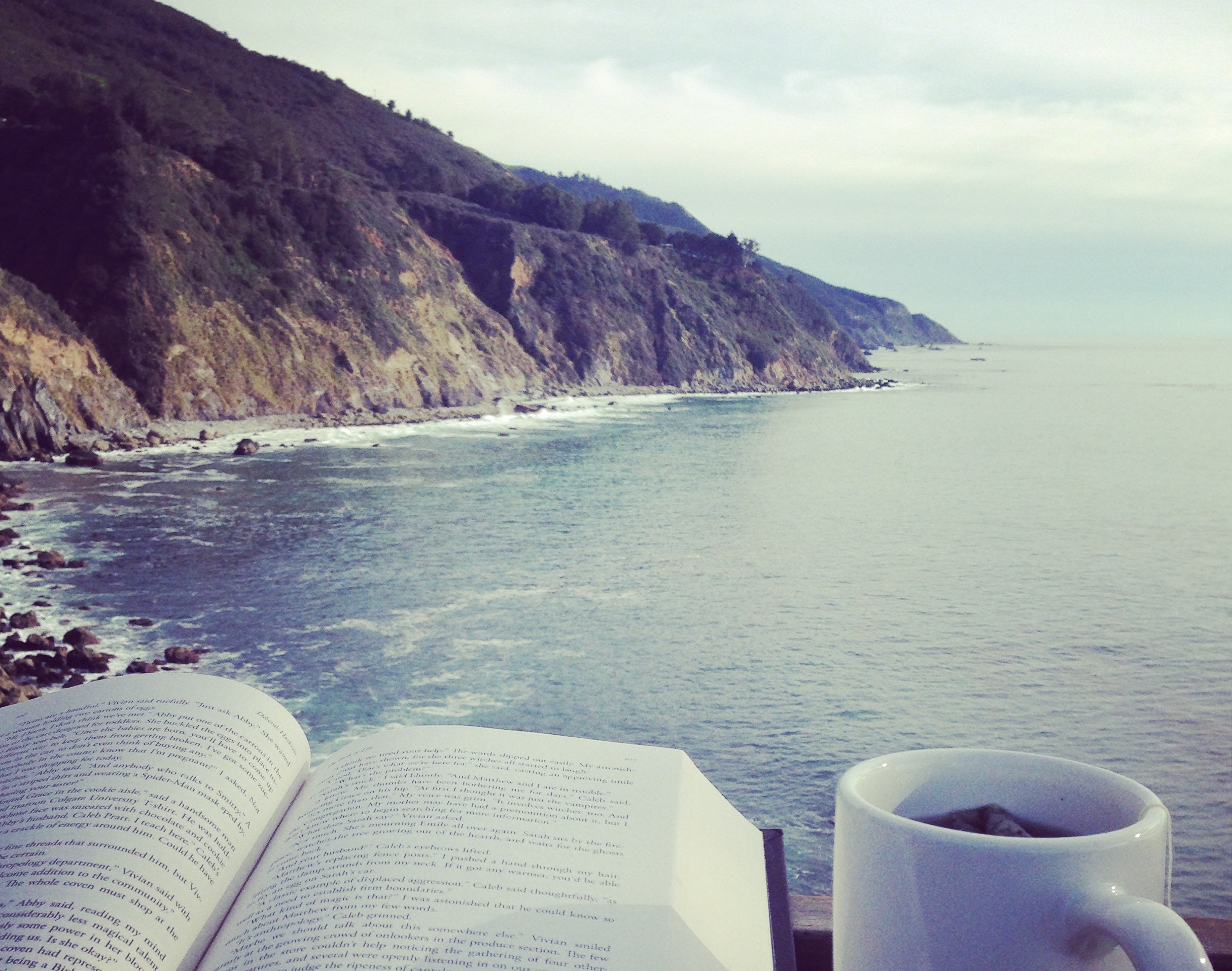

Dad lived up in the Santa Cruz mountains, miles down a dirt road, on ten acres of land that includes redwoods and a stream. Not bad, if you like that kind of thing. I remember lying in a hammock strung between two redwoods and reading Calvin & Hobbes in the sun. I would go stone hopping along the creek, followed by one of Dad's more adventurous cats.

Going through his stuff after he died, I began to fully understand some of our shared character traits. Dad had tons of educational materials he bought and never opened. So do I. He thought about writing a novel for years - we talked about it and he had copious and carefully organized plot notes. As far as I can tell, he died before he wrote the first chapter.

It's a form of resistance. You take the first step and then you drag your feet on taking the second step - sometimes for years. But what I've learned since is that you can always make a new choice. Just because Dad didn't ever start his novel doesn't mean I won't ever finish mine. Just because he never cracked open his audio courses on world religions doesn't mean I have to go to my grave having never finished reading my copy of Die Empty. It's easy to get lost in the comforting warmth of familial bonds, but his choices do not have to be mine. His struggles don't have to dictate my eagerness to build and create and learn.

Dad loved fantasy and science fiction. Sick to death of endless recitations of Goodnight Moon, he read me The Hobbit when I was three years old. I'd sit on the couch next to him with my sippy cup and security blanket and absorb tales of trolls and wizards and rings of power. He had vast bookshelves of the stuff and spent years upon years developing ideas for his own series without ever putting a word to paper.

He left behind a lot of stuff. My question is, what did he take with him?

Stephenie Meyer says her Twilight series came to her in a dream, and she transcribed her world of glittering vampires and adolescent fantasy onto paper and sold millions upon millions of copies. I like to think that will happen to Dad in his next life. That he'll wake up one morning and the plot line he spent years upon years developing in this life will burst into his brain fully formed, and all he'll have to do is copy it down. So maybe the work of this life won't be lost.

If you want to extrapolate wild theories based on a belief in reincarnation and soul memory, this could explain people like Mozart. You spend years, decades, lifetimes learning the rules, practicing the notes, playing the scales. Maybe you spend three deeply aggravating lifetimes being on of those people who tries and tries and never quite make it - and then you get born Adele and win Grammies and Oscars in your early 20s, after making the whole world shake with your music. I don't know. But I like to think that's possible and that my dad will get to see his work in print, even if the author plate holds a different name and picture.

Isn't that a nice thought? That even if you die without fulfilling a dream, all your work of this life could pay off in the next. Maybe nothing is wasted. So if you love something, do it. If you're bad at it, who cares? Even if you haven't the slightest hint of talent, practice as hard as you can. Maybe it will pay off two hundred years from now when you look completely different and have a license for a flying car. Maybe I should keep singing in the shower. Just because I sound like a choking alley cat doesn't mean that a few rounds from now I won't be Taylor Swift.

I like to think that maybe my dad will be born into another body in ten, twenty, fifty years and he'll want to be a writer, and that plot and world that he spent decades of this life developing and dreaming and researching will come to him, fully formed, like it was coming from another time or place. Maybe he won't understand it but he'll trust it and run with it. And the book he wanted to write in this life will be written in his next.